|

Book Review

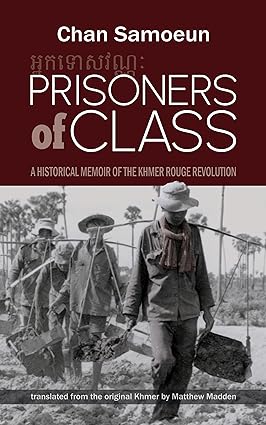

I became aware of this book in the latter half of 2022 when the translator of the original Khmer text, Matt Madden, got in touch. Over the next few weeks and months, he shared with me some early drafts of what he was working on, as well as some insights into the book and its author Chan Samoeun. However, now that I am looking at a physical copy, and having re-read it in its entirety over the last few days, I feel better acclimated to the whole work and feel that I should prepare a review of this important and touching memoir of survival during the Cambodian nightmare. For the sake of transparency, I will say that Matt was generous enough to provide my copy of the book free of charge (although I did pay for the Kindle edition so I could read it on a recent holiday). I am also one of a few persons who provided a blurb for the book and was pleasantly surprised to see my name pop up in the translator’s acknowledgements. In the not distant future, there are also plans to have Matt on the podcast to discuss the book, amongst other topics. So, consider yourself privy to any behind the scenes collusion. With that said however, I did not actually have plans to write something like this until just a few days ago as I neared the completion of the book again. Prisoners of Class is one of the best memoirs of the Khmer Rouge revolution, and I would personally rank it alongside Pin Yathay’s ‘Stay Alive My Son’. It is unique in many ways, but the most important aspects relate to the facts of where and when it was written. Chan Samouen was not a refugee, and his memoir reads more like a diary than a story, the writing is not intended for a Western audience. Given that it was written so soon after the collapse of the regime, its value as a historical source is tremendous. It reads differently than what you might be used to, “Characters”, on the “stage of the Cambodian tragedy” (to borrow similar phrasing to the author) will arrive and leave often without the kinds of narrative flourish that might be present in other similar texts. Similarly, the writing will often be repetitive, poetic, or obsessed with minor details or ‘scenes’ that might not have been considered relevant in books that were written with either a western influence or indeed for a western audience. I must admit that the first time reading the book, and particularly in some sections of the first and second parts, the writing can be a little hard to acclimatize to. However, this second read through, I felt more accustomed to the style and the way in which the author relays his story. Taken as a part of a whole, what might be considered a monotonous chapter about a particular day of labor and the particular texture of a rice porridge or the various insects and reptiles that could be found in the mud or marshes, can be seen as a part of a larger rhythm to the experience of a ‘life slave’, as he coined the ‘new people’ class he lived in. While historians, and the author himself also notes in the book, everyone who went through the revolution has their own story. There are millions of them, each unique, each sharing much of the same. But I felt that there was something unique here that I had not found elsewhere. That is not to say that this book is sadder, or more graphic, or has stronger writing or even more of an insight into ‘what was happening’ while it was happening – but there is something to Prisoners of Class that makes it stand out. Perhaps it is the lack of ‘story’, or perhaps a better word would be ‘narrative’. There is no climactic escape like at the end of Stay Alive My Son, there is no central, emotionally tragic event like in First They Killed My Father or Survival in the Killing Fields. Obviously, all of these are true stories and are not embellished, but there is a certain way that this book in particular is relayed that feels as though you are reading someone’s diary as opposed to their memoir. Characters who you may think will prove to be ongoing antagonists or protagonists, might simply (and unceremoniously) disappear in the day or the night, or simply stop appearing in the pages for no better reason than they are just not in the story anymore. The main character might be sick for months at a time, describing the hellish conditions of a Khmer Rouge ‘hospital’, and once he gets marginally better, only relapses into illness once again. The ‘story’ as it is, might go on slightly, only to meander back into writings of sickness as the author once again became sick. It is not forced or edited into a narrative arc, the author simply kept getting sick and that is what the story necessarily focuses on. Work is embarked upon, sometimes mastered, only for it to change or become harder or to be conducted elsewhere. Khmer Rouge cadre are sometimes fearsome, and sometimes benign – many offer care and sympathy – many brutalize and kill. The author is picked up and put into so many different work brigades and labor projects that many settings blur into seasonal tales of digging, cutting, harvesting, tending to animals, of being thirsty, hungry, starving, full, wet or dry, sick, infected or injured. All of these themes and settings are not unfamiliar to those familiar with the wider Khmer Rouge survivor memoirs, but here it seems to be represented more ‘as is’. Anyone who may feel that the first part of the book is becoming a slog, I beg you to keep going. The book is a tapestry of the dead and dying, woven into the truly nihilistic four years of pain and suffering that the country and its inhabitants endured. It is a reflection of that life, it has no central point it tries to prove and rarely acts as though it is a story for anyone else but the author. Of course, it is still a testament to the crimes against humanity that were inflicted on Cambodians, and it stands as a historical document of that – these are central points of course – but it does not go out of its way to prove anything more than the deadly mundanity of the nightmare as it often was experienced as. The life slave thought of almost nothing but food, of how to live each day, of how to survive the gaze of cadre looking for enemies. Although it does not go out of its way to find resonant emotional themes, it nevertheless has the tragedy, it has the deaths, it has unrequited love, constant fear, and guilt and shame and regret. The author rarely states what insights into the workings of Democratic Kampuchea he has, but through his writing of his day-to-day experience, I found many interesting intersections between the broader history of the regime and his microcosm of life within it. It is written in almost poetic phrases at times, and in fact does contain numerous poems and songs that the author punctuates scenes or the ends of chapters with. It is somewhat difficult what words to put this into, but Prisoners of Class is a book about the Khmer Rouge revolution that avoids much of the background noise of western associations of “the Khmer Rouge” or “Pol Pot” as concepts that the reader is generally already familiar with. It neither speaks down to, or up to, established ideas that one might have. It does not often take care to do so (although thankfully for the uninitiated the excellent translator has provided valuable footnotes to explain either Khmer language concepts or important context throughout). The book, in isolation, says everything about the horrors of the regime, but in a way that is almost equivalent to the language of movies in that it often ‘shows’ rather than ‘tells’ the audience. The amount of intention here, I do not know, but as someone who has read many memoirs of the events – whether in books like those mentioned, or confessions of prisoners at S21, or in refugee statements or witnesses at the Khmer Rouge Tribunals… Chan Samoeun’s Prisoners of Class stands out to me. I am grateful that it has been translated into English for the first time, and I am grateful that the author wrote it. He himself questioned the decision to do so, as many people ‘in history’ don’t often think it necessary to write their history… He has provided a valuable historical document, and a moving personal story, another voice in a decreasing chorus of those who can share their story of how they lived through the Cambodian nightmare. You can purchase the book through https://www.mekongriverpress.com/ as a physical copy or an eBook.

0 Comments

Here is an attempt to correct some numbers, in 2006 Kiernan wrote in an article for "The Walrus", that according to some estimates they could calculate that there were more than 2.5 million tons of ordinance dropped on Cambodia from 1965-1973.

Four years later, they corrected this number because they had used 'mistaken technical analysis'. They had miscalculated by about 5 times (if my maths is correct). From 2.5 million tons, this was reduced to 500,000 tons. This is detailed in this article in the Asia Pacific Journal, by Kiernan https://apjjf.org/Ben-Kiernan/4313.html Here is the relevant quote from Kiernan: During 2000-2010 various estimates, including ours, of the U.S. bombing tonnage dropped on Cambodia from 1969 to 1973 followed a trajectory similar to High’s up-down estimates for Laos. And for similar reasons: the difficulties of technical analysis of the Pentagon’s enormous but antiquated Southeast Asia bombing databases. In 1989 one of us (Kiernan) had published an article calculating a figure of 539,000 tons dropped on Cambodia.13 But in 2000, just as High did for Laos eight years later, the Phnom Penh Post reported a new Cambodia total, a dramatic upward revision: “The [data] tapes show that 43,415 bombing raids were made on Cambodia dropping more than 2 million tons of bombs and other ordinance.”14 This figure had significant implications for the continuing work to clear the Cambodian countryside of the still widespread, deadly unexploded ordnance (UXO), as well as for a historical understanding of the wartime humanitarian and political impact of the US carpet bombings. Our 2006 article, “Bombs over Cambodia,” using the same database and analysis, calculated a figure of 2.7 million tons dropped on Cambodia in 1965-75.15 Our estimate, published in the Canadian magazine The Walrus, and in 2007 in The Asia-Pacific Journal, was widely quoted. But in 2010 we corrected that estimate, here in The Asia-Pacific Journal. We revised it back down to around 500,000 tons.17 In doing so we took account of the mistaken technical analysis that had impacted bombing tonnage estimates for both Laos and Cambodia. Holly High had written to Kiernan on January 4, 2010: “I have been working with computer scientists here at Sydney and we have managed to make a fairly responsive database and also account for the anomalies in the data . . . The database covers all of Southeast Asia, and contains many more fields than the data that you were working with, from what I can tell from the data on the Cambodian Genocide Project website. It looks like the data you and others in the UXO business were provided with was a simplified, distilled version of the original SEADAB and CACTA files [combined Pentagon databases entitled “Records About Air Sorties Flown in Southeast Asia,” and “Combat Air Activities”], sorted country by country so that each nation received only “its” records. The original database is much larger: indeed it is simply massive. It is also deeply flawed (some of the data appears to have been corrupted and there are omissions in certain months).” Kiernan wrote back to High on January 18, 2010 stating that “we would urgently like to incorporate corrections of mistakes that were based on faulty Pentagon data, and show where that data is inaccurate. If it is okay with you, we would of course like to credit you and your skilled research assistant at Sydney Uni’s Faculty of Information Technology, who has worked on this with you, for bringing the database errors to our attention. Obviously the sooner we correct those the better.” In an email of March 1, 2010, High asserted that in the Pentagon’s SEADAB database, the original entries for each sortie under the field of bombing “Load Weight” had been incorrectly keyed in, with a zero mistakenly added to each figure. Those bombing tonnages thus had to be divided by ten. In June 2010, therefore, we published our downward correction of our 2006 estimate of 2.7 million tons. We stated that “this tonnage data may be incorrect. In new work using the original Air Force SEADAB and CACTA databases, Holly High and others have re-analyzed the total Cambodia tonnage figures and argue in a forthcoming article that the total tonnage dropped on Cambodia was at least 472,313 tons, or somewhat higher.” We concluded: “It remains undisputed that in 1969-73 alone, around 500,000 tons of U.S. bombs fell on Cambodia.” I'm writing this blog post about it in the hopes that the original figure is no longer casually shared, because as Kiernan says, it often is... but this correction is rarely sought out or provided. Hi everyone, had kind of forgot there was a blog section of the website... and that last post is grim ! haha. Wasn't the best time... and I think we've had like 7 episodes or something since then so, don't worry, it kept going. But, when I took about 3 minutes to figure out something to write as a blog piece to make that last one not the top one still, the only thing I could really think of was, oh, I forgot, I've been doing this for more than FIVE YEARS! While this isn't exactly a "job", I think this is now the longest job I've ever had, and its a while off still from an ending. So I just wanted to say a few things about those five years. Firstly, I have learned a lot in this time. That has been the biggest thing. I thought I used to know some things about Cambodia when I started, now I realise just how little I knew then. This has been the best learning exercise I could have done. Secondly, I think the more I do this, the more books, the more sources, the 'better' I get at this, it does seem to take longer. Episodes take a lot of research, they run into the tens of thousands of words for a script, the editing takes days... You'd think I might have been able to shorten that amount of time, but I suppose having other jobs or responsibilities also influences that a lot. But, yeah, I think they are better researched, and get at the complexities of the modern history more... perhaps because I was more aware of these previously, but either way, I hope the quality is coming along. Thirdly, it has been so rewarding being able to ineract with people, with listeners, other podcasters, survivors, sons and daughters of Cambodian refugees, students, journalists, historians and fellow Cambodia lovers generally. It is such a pleasure. Not to mention being able to use listener donations to support two different charities in Cambodia, genuinely making a difference for people and animals. That makes me very happy to have put so much time and effort into this multi-year project. While I've gotten used to 'the process', I still have many moments of fascination, energy and excitement when I continue to research and produce it. Thank you to everyone who has listened. Here is an unrelated picture of me in Mexico where I now live: Hi everyone, I guess there might be a percentage of those who listen to the show at the moment who might be wondering what is going on and why there hasn’t been a new episode in awhile.

I had released a statement on Patreon awhile back which addressed this but it makes sense to do so here as well. Basically, this is a hobby of mine, not a full-time job nor something I can devote 100% of my time to. I’ll keep this brief and simply say that, well… I have not had the mental space nor the time to work on the show for the last two months. The next episode, as it stands, is about half-way done, and the show will continue. I appreciate your patience as I find the time to work on it and release it in due course. All the best, Locky Am I comparing my podcast to the original Star Wars trilogy? Yes.

So, following on from the previous blog post, having listened to one of the early episodes and having a bit of anxious moment about some of the things in there... I decided to pull a George Lucas and go back and change some things. I didn't go full Greedo shoots first, I didn't digitally reintegrate an alien rock band into Jabba's palace... but I didn't stop at simply cleaning up the audio either. All in all, I had wanted to go back and fix a few things for a very long time now, and having recently purchased some new audio repair software I felt this was a good time to do so. I had not found a rhythm in how to record back then, I did not know some very basic things to make editing easier or create a better sounding end product. But more than that, I had also made some quite strange decisions regarding the tone of the show and I think that stemmed from a lack of confidence about what I wanted the show to be. I can remember worrying very much that people would simply turn the show off if there wasn't more... excitement. I felt I constantly had to have some kind of background music, or make jokes throughout, or use language more appropriate for a kind of chat show rather than a history podcast. I didn't quite know what the tone of the show should be in these early episodes, and I may have covered up my own lack of knowledge about early Cambodian history with excessive generalisations. I was most happy with the introductory episode, I think it still stood up really well. I didn't re-record any dialogue for that episode, merely fixed up some background noise issues and some of the pauses between phrases. The two episodes about Angkor however, these are the ones that I remember quite frantically putting together and thinking that people would be bored by, so I took on this kind of... jokey tone. I left the simpsons quote in the first one (after putting it to Twitter and hearing that people actually really liked it) but I re-recorded some things and took out the excessive background music that played over some sections of audio. I did a similar thing in the second episode with the explanation of Zhou Daguan's book, I remember even back then I had already done a re-release after I left in way too much joking about the more salacious things that the Chinese diplomat had included. This whole bit needed work because I think back then I had just taken stuff out, but then kind of referred back to that stuff later, which didn't make sense. I might continue doing this process in the future. It took me about three and a half days to fix up just three episodes so maybe after the release of the next one I might go back and see if another one or two need anything cleaned up. It is one of the problems with doing this over... what three and a half years? Like you get better at that thing while you do it, but because it is a linear series with a set of episodes that you kind of have to go through one by one, well if those early ones aren't that good then people don't bother continuing with the show. I had always wanted to have giant Dewback lizards in the background of most episodes, but I just didn't have the time or skill to do so. I decided to go back and listen to the second episode I released, which was originally I think in early 2018. It was about the Khmer civilisation leading into the Angkor period. It was... strange, it felt like reading an old diary or something of that nature... was that really me who came up with some of these creative decisions?

Tips for anyone thinking of making a history podcast - number one - resist the temptation to use excessive sound effects or background music. I don't know why I felt the need to have most of this episode set to music or sounds... there is a section at the end that just has the sound of rain for like 5 minutes? And the music under some of the discussion of the early Khmer kings was overbearing. I think I felt like nobody would keep listening if there were not interesting sounds - and I think that might explain the Simpsons gag as well. The dialogue itself though, I was surprised I didn't have too much that I would change? There was the occasional stumble, and I think as I was generally less familiar with that early Cambodian history as I am now I might have fallen into a couple of the common misconceptions - like I mentioned that scholars use the phrase 'dark ages' of Cambodian history - which none do anymore. I brought this up on twitter, saying that podcasting itself was quite a strange medium in this way. Like, I started this project three years ago, but it was as if I had been writing a book that I had to publish each chapter at a time... without being able to go back and change what I had written even if the story itself had evolved in new directions. Happily someone pointed out that this was one of the benefits as well - that once you have written a book the whole thing is done and thats it, you don't have the ability to change course over time. I guess I think of those early episodes a bit like the first season of a TV series, sometimes it can be awhile before the show finds its feet and direction. I'm glad that even though I might not like some of the earlier stuff, my tone is a bit all over the place and the amount of sources I had was minimal... I guess it was just necessary to get started and start that journey even if the content wasn't as polished as it could be. And if people like it enough they will see it get better over time. I just hope I don't look back at the episodes I am releasing now and think the same thing in three years time! Check out the interview I did with Lina Goldberg of 'Move to Cambodia' fame!

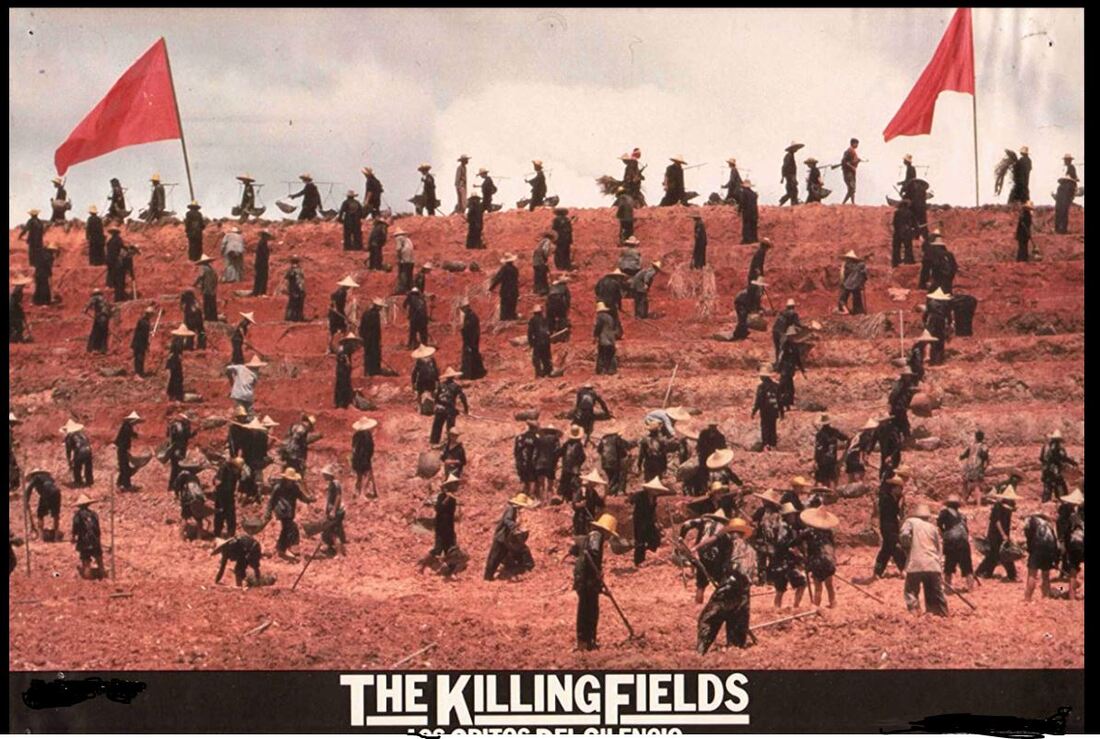

https://www.movetocambodia.com/art-culture/in-the-shadows-of-utopia-cambodian-history-podcast/ In year ten history class, my teacher Mr Kingsley put a video tape of the “The Killing Fields” on that we watched over a couple of lessons. I look back now and wonder just how important that was for my life, would I be sitting here now, fifteen years later, writing a review of the film as part of my own project to explain Cambodian history and the Khmer Rouge to a wider audience? Probably not. I think I owe this movie something for the journey that it influenced me taking.

There are a few things you can say about the film that are hard to argue against. For instance, I believe it is the best ‘movie’ about Cambodia made in the West, not that there are very many. It is also fair to say that it is an important movie, and the impact that it raising awareness about the tragedy that had occurred in Cambodia was beneficial. It is admirable in its attempt to recreate locations, events and people to a highly accurate degree. Lastly, I think the portrayal of Dith Pran by Haing Ngor is one of the bravest pieces of acting ever put to screen. Fifteen years since I first saw it, I would say that I have probably watched the movie more than ten times. Then, in preparation for a ‘commentary track’, I’ve made more of an effort to research the film itself and the characters portrayed in it, watched it through a slightly different ‘lens’ as they say. I re-read The Death and Life of Dith Pran, the article turned into a book written by Sydney Schanberg and the material which the screenplay is based, as well as Haing Ngor’s Survival in the Killing Fields, Jon Swain’s River of Time and also watched the Khmer Rouge Tribunal footage of Sydney Schanberg and Al Rockoff’s testimony. I tried to formulate my own ‘take’ on the film that I had previously not really bothered to do. I had, more or less, just viewed it as a good movie about a subject I care a lot about. My ‘thoughts’ about the film have been influenced very much by Al Rockoff, the photographer played by John Malkovich, in an answer to a somewhat bizarre question given the setting of an international tribunal of the Khmer Rouge leadership. When asked by the defence for Nuon Chea if he had seen the film, Rockoff went on a small tangential rant: “I always get asked that. For the first time back here in 1989, I keep getting asked, ‘you see killing fields? You see killing fields?’ I walk down the street, the tuk tuk drivers, ‘you see killing fields?’, of course I’ve seen the movie, many times. I have my own thoughts on the movie that may not be shared with the public because of how I’m portrayed in the movie. But I consider it a work of art. I might find some fault with how certain personalities are represented or certain facts. But its an important movie.” It is an important movie, even if some fault can be found with certain representations. I like The Killing Fields as a movie, it is an important movie with an important theme – but it is a movie. So my criticism of it as history must be tempered by that fact, that it was designed first and foremost to be a compelling experience for your average movie goer – not for the majority of Cambodians, historians or those with an interest in what happened in Democratic Kampuchea. However, the film – like historical writing – does decide what it shows and what it doesn’t, it frames the narrative in certain ways so that your average viewer comes away with an impression of a historical event. For instance, the impression we get of Phnom Penh and Cambodia generally is entirely focused on the US presence, the excess of US bombing, the failure of the US to stop the Khmer Rouge and finally in no uncertain terms Schanberg later blames the insanity of the KR on the effect of a few million tonnes of bombs dropped on them. Perhaps the cultural context in which the film was made explains some of that angle, the collective need to denounce the US after the Vietnam War, the lack of faith in government, the anti-war movement generally. But because the film is limited in its scope by its reference point of a western journalist bemoaning the way he treated his Cambodian colleague, we get an underwhelming explanation of what else happened or why it happened. Was the US involvement in Vietnam and Cambodia a contributing factor to the Cambodian nightmare? Sure, but it was one of many. The film also diverges from its own source material in some cases where, if it hadn’t, the whole story might have been made more apparent. In reality, Dith Pran’s exit from the French Embassy lacked a contrived scene of attempted photograph development, but it was no less dramatic. His throwing away of several thousand US dollars, taking on his new identity and getting through a KR checkpoint among the thousands of evacuees from Phnom Penh would have been very interesting to watch. Instead, in perhaps the film’s weakest scenes, the focus is placed on Schanberg in New York. We watch him regret, we watch him slump in a chair. We would have been able to guess his emotional state following his return to the US, but instead we need to be shown that the story is just as much about the US as it is about Cambodia, footage of Nixon, bombs and carnage leaving the audience with a graphic finger pointed at the reason for Democratic Kampuchea. The film spends roughly a quarter of the second half of the film still following the ‘main character’, Schanberg. This, in my mind, was an opportunity to commit to the Cambodian side of this tragedy, experienced by Cambodians, but the script still demands our viewpoint to be concerned with how bad the US should be feeling at this time. Again, here we come back to the idea that his is a movie, but the lack of subtitles in the Democratic Kampuchea section of the film still places the viewer as the outsider, as the westerner (generally speaking) who must watch in horror as the Cambodians descend into ‘insanity’ because of things we’ve done. Rather than a project that they decided upon and implemented. The other aspect of the film that I think does need to be criticised – even if it is primarily a movie – is the lack of violence. Cambodian audiences, historians and even those acting in the film (Haing Ngor) voiced their opinion that the film did not go far enough in its depiction of the brutality of the Khmer Rouge. You can notice in a few scenes the stunted length of Haing Ngor’s right pinky finger. That part of his finger was cut off during one of his three stints in a rural Khmer Rouge prison near Battambang. The other acts of violence he was witness to at these prisons are some of the most extreme that one can find in studying the regime. And while depicting acts of torture and gruesome violence itself may not have been possible due to ratings concerns, the film does not show the non-violent brutality of the regime. The masses of starving, the sick and the slowly dying. We are shown ‘the killing fields’, in a tremendous scene yes, but prior to this Pran is helped by a friendly young cadre and after his escape we have him in the company of a moderate commune chief. The percentage of time spent to showing the Khmer Rouge as violent killers is comparable to the amount shown of their accommodating nature. Yes, black and white, victim and perpetrator, these binary distinctions in a period of mass death lack applicability, but I feel the movie does not quite explore this theme satisfactorily – and perhaps goes too far in its attempt to show the grey area, rather than the tragic demise of more than a quarter of an entire population at the hands of one group – the Communist Party of Kampuchea. Alas, it is a movie, and it is a movie that I like very much. I wish it could have shown more of the story as it really happened, but perhaps that is only because I have learned far more about that story since I first saw the film. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the country, but I would certainly not tell them to stop there. A Question on Reddit by u/DrCharlesTinglePHD)

I'm wondering about this because I have read differing estimates of the count, and differing estimates of the various causes (starvation, murder, etc.). I have many books on Cambodian history, but what I believe to be the most trustworthy one (A History of Cambodia, 4th edition, by David Chandler) is probably out of date. Also for context, what was the population of Cambodia before Lon Nol took over from Sihanouk? And do we have any idea what was it when Pol Pot took over from Lon Nol? I'm also interested in the count of executions by motivation - e.g. how many were killed because they were Vietnamese, how many were killed because they were the wrong class, how many were killed for no reason at all, etc. Answer I would say that the most recent, well researched and accurate estimates of the death toll in Democratic Kampuchea came out of the Demographic Expertise Report titled Khmer Rouge Victims in Cambodia April 1975 - January 1979 by Tabeau and Kheam. This report was compiled as part of the proceedings of the ECCC and the Office of Co-Investigative Judges. It is an assessment of most, if not all, of the major estimates made of the death toll by various sources and includes much of the information you seek, including cause of death (indirect versus direct), estimates of population sizes and evidence which can be used to base these assessments. I will be using this document to answer the questions you have but feel free to read it yourself as it can be downloaded here. Death Toll The report does not differ too much from the more common overall estimates that you would probably already find in the sources you own, indeed in the one you believe ‘most trustworthy’, Professor Chandler states that Life was hard everywhere. On a national scale it is estimated that over the lifetime of the regime nearly two million people – or one person in four – died as a result of DK policies and actions. The Demographic Expertise Report places the estimate of the death toll under the Khmer Rouge to be most likely 1.747 to 2.2 million. This estimate is based on the most reliable methods, including projections of population growth based on statistics data prior to and following the regime’s time in power, as well as the death toll linked to mass grave records. This is coupled with research reports, surveys, survivor’s accounts and relevant expert opinions from NGOs and independent researchers. Estimates which posit numbers vastly below this, such as Michael Vickery’s, can come from using a much lower population size at the beginning of the regime. They can also be influenced by what the expert demographers say would be ‘some pre-determined views on what kind of outcome should be obtained’ (read as biased and agenda driven). Population Prior to DK The population estimates which the experts find most reliable for the period prior to the regime coming to power (April 1975) is 7.844 to 8.102 million, with the central value of 7.894 million. The population estimates of 1970 (beginning of Lon Nol Period) are from 7-7.662 million. The death toll estimate they feel is most appropriate for the civil war is 250,000, which is generally lower than what is usually given in figures which often exceed half a million. Causes of Death As the most likely estimate of about two million deaths is given, you would no doubt be familiar with ideas about how these excess deaths occurred. Starvation, overwork and disease were all prevalent in DK, and much of this prevalence is explained through policies of the Khmer Rouge. What the Demographic Expertise Report suggests however, is that the weighting of these ‘excess deaths’ to ‘direct deaths’ (meaning from violence/executions) may be more even than in earlier estimates. They conclude, and using mass grave data as evidence, that the violent deaths at the hands of the Khmer Rouge may account for at least 1.1 million deaths. So at least 50 percent of the death toll was the result of execution. Unfortunately, it is harder to ascertain the answers to some of your follow up questions regarding why certain deaths may have occurred. All that you can work back from are statistics about different ethnic population sizes or in the case of policies relating to targeting ‘class enemies’ (such as the New People/April 17 People) how many from urban backgrounds can be counted before and after the regime. For instance, if there were two million urban Khmer as part of the ‘New People’ category defined under DK, and 500,000 perished, you can make assumptions about that cause of death relating to class status, but you cannot pinpoint the actual reason they died. They died at a higher rate, for various reasons. There is a similar case in relation to ethnic minorities, and the Demographic Expertise Report notes that Kiernan’s estimates are most convincing, as are his opinions about why they may have been targeted at a higher rate. But they do recognise that there is a degree of uncertainty about the estimates as there are a lack of reliable sources on ethnic groups in Cambodia in the 1970s. Generally it is thought that the remaining Vietnamese within the country, perhaps around 20,000, were all killed during DK. Again, whether 100% of those deaths were the result of these people being targeted on the basis that they were Vietnamese, is hard to nail down. In an interview I conducted with Professor Chandler in 2018, he claimed that Kiernan’s numbers were subject to significant estimation, based on very little. Watch that interview here Conclusion The general estimate of 1.75-2.2 million dying, either indirectly or directly, in DK that has been given in most reputable sources on the matter in the last few decades still holds true. In fact with projects like DCCAM’s Mass Grave Mapping, these estimates have become better evidenced than when they were originally made and can be used to claim even more violent deaths at the hands of the regime than previously thought. While we will never know how many died for precise reasons, the numbers of who were more likely to die and perhaps what policies influenced that treatment are substantiated. If we take the number of those dying directly at the hands of the regime, and presume these killings to be ideologically motivated, than we can say somewhere in excess of one million people were killed for these political reasons during the roughly four years of DK. The most generalised reason you could give to account for their deaths would be under the heading of ‘counter-revolutionaries’, which would take into account killings for breaking rules, for not having the right class background, for being an ethnic or religious minority or a suspected traitor to the regime. |

AuthorLachlan Peters Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed