|

Book Review

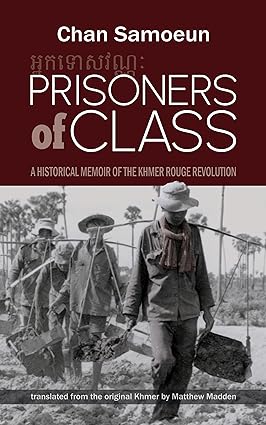

I became aware of this book in the latter half of 2022 when the translator of the original Khmer text, Matt Madden, got in touch. Over the next few weeks and months, he shared with me some early drafts of what he was working on, as well as some insights into the book and its author Chan Samoeun. However, now that I am looking at a physical copy, and having re-read it in its entirety over the last few days, I feel better acclimated to the whole work and feel that I should prepare a review of this important and touching memoir of survival during the Cambodian nightmare. For the sake of transparency, I will say that Matt was generous enough to provide my copy of the book free of charge (although I did pay for the Kindle edition so I could read it on a recent holiday). I am also one of a few persons who provided a blurb for the book and was pleasantly surprised to see my name pop up in the translator’s acknowledgements. In the not distant future, there are also plans to have Matt on the podcast to discuss the book, amongst other topics. So, consider yourself privy to any behind the scenes collusion. With that said however, I did not actually have plans to write something like this until just a few days ago as I neared the completion of the book again. Prisoners of Class is one of the best memoirs of the Khmer Rouge revolution, and I would personally rank it alongside Pin Yathay’s ‘Stay Alive My Son’. It is unique in many ways, but the most important aspects relate to the facts of where and when it was written. Chan Samouen was not a refugee, and his memoir reads more like a diary than a story, the writing is not intended for a Western audience. Given that it was written so soon after the collapse of the regime, its value as a historical source is tremendous. It reads differently than what you might be used to, “Characters”, on the “stage of the Cambodian tragedy” (to borrow similar phrasing to the author) will arrive and leave often without the kinds of narrative flourish that might be present in other similar texts. Similarly, the writing will often be repetitive, poetic, or obsessed with minor details or ‘scenes’ that might not have been considered relevant in books that were written with either a western influence or indeed for a western audience. I must admit that the first time reading the book, and particularly in some sections of the first and second parts, the writing can be a little hard to acclimatize to. However, this second read through, I felt more accustomed to the style and the way in which the author relays his story. Taken as a part of a whole, what might be considered a monotonous chapter about a particular day of labor and the particular texture of a rice porridge or the various insects and reptiles that could be found in the mud or marshes, can be seen as a part of a larger rhythm to the experience of a ‘life slave’, as he coined the ‘new people’ class he lived in. While historians, and the author himself also notes in the book, everyone who went through the revolution has their own story. There are millions of them, each unique, each sharing much of the same. But I felt that there was something unique here that I had not found elsewhere. That is not to say that this book is sadder, or more graphic, or has stronger writing or even more of an insight into ‘what was happening’ while it was happening – but there is something to Prisoners of Class that makes it stand out. Perhaps it is the lack of ‘story’, or perhaps a better word would be ‘narrative’. There is no climactic escape like at the end of Stay Alive My Son, there is no central, emotionally tragic event like in First They Killed My Father or Survival in the Killing Fields. Obviously, all of these are true stories and are not embellished, but there is a certain way that this book in particular is relayed that feels as though you are reading someone’s diary as opposed to their memoir. Characters who you may think will prove to be ongoing antagonists or protagonists, might simply (and unceremoniously) disappear in the day or the night, or simply stop appearing in the pages for no better reason than they are just not in the story anymore. The main character might be sick for months at a time, describing the hellish conditions of a Khmer Rouge ‘hospital’, and once he gets marginally better, only relapses into illness once again. The ‘story’ as it is, might go on slightly, only to meander back into writings of sickness as the author once again became sick. It is not forced or edited into a narrative arc, the author simply kept getting sick and that is what the story necessarily focuses on. Work is embarked upon, sometimes mastered, only for it to change or become harder or to be conducted elsewhere. Khmer Rouge cadre are sometimes fearsome, and sometimes benign – many offer care and sympathy – many brutalize and kill. The author is picked up and put into so many different work brigades and labor projects that many settings blur into seasonal tales of digging, cutting, harvesting, tending to animals, of being thirsty, hungry, starving, full, wet or dry, sick, infected or injured. All of these themes and settings are not unfamiliar to those familiar with the wider Khmer Rouge survivor memoirs, but here it seems to be represented more ‘as is’. Anyone who may feel that the first part of the book is becoming a slog, I beg you to keep going. The book is a tapestry of the dead and dying, woven into the truly nihilistic four years of pain and suffering that the country and its inhabitants endured. It is a reflection of that life, it has no central point it tries to prove and rarely acts as though it is a story for anyone else but the author. Of course, it is still a testament to the crimes against humanity that were inflicted on Cambodians, and it stands as a historical document of that – these are central points of course – but it does not go out of its way to prove anything more than the deadly mundanity of the nightmare as it often was experienced as. The life slave thought of almost nothing but food, of how to live each day, of how to survive the gaze of cadre looking for enemies. Although it does not go out of its way to find resonant emotional themes, it nevertheless has the tragedy, it has the deaths, it has unrequited love, constant fear, and guilt and shame and regret. The author rarely states what insights into the workings of Democratic Kampuchea he has, but through his writing of his day-to-day experience, I found many interesting intersections between the broader history of the regime and his microcosm of life within it. It is written in almost poetic phrases at times, and in fact does contain numerous poems and songs that the author punctuates scenes or the ends of chapters with. It is somewhat difficult what words to put this into, but Prisoners of Class is a book about the Khmer Rouge revolution that avoids much of the background noise of western associations of “the Khmer Rouge” or “Pol Pot” as concepts that the reader is generally already familiar with. It neither speaks down to, or up to, established ideas that one might have. It does not often take care to do so (although thankfully for the uninitiated the excellent translator has provided valuable footnotes to explain either Khmer language concepts or important context throughout). The book, in isolation, says everything about the horrors of the regime, but in a way that is almost equivalent to the language of movies in that it often ‘shows’ rather than ‘tells’ the audience. The amount of intention here, I do not know, but as someone who has read many memoirs of the events – whether in books like those mentioned, or confessions of prisoners at S21, or in refugee statements or witnesses at the Khmer Rouge Tribunals… Chan Samoeun’s Prisoners of Class stands out to me. I am grateful that it has been translated into English for the first time, and I am grateful that the author wrote it. He himself questioned the decision to do so, as many people ‘in history’ don’t often think it necessary to write their history… He has provided a valuable historical document, and a moving personal story, another voice in a decreasing chorus of those who can share their story of how they lived through the Cambodian nightmare. You can purchase the book through https://www.mekongriverpress.com/ as a physical copy or an eBook.

0 Comments

|

AuthorLachlan Peters Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed