|

Check out the interview I did with Lina Goldberg of 'Move to Cambodia' fame!

https://www.movetocambodia.com/art-culture/in-the-shadows-of-utopia-cambodian-history-podcast/

2 Comments

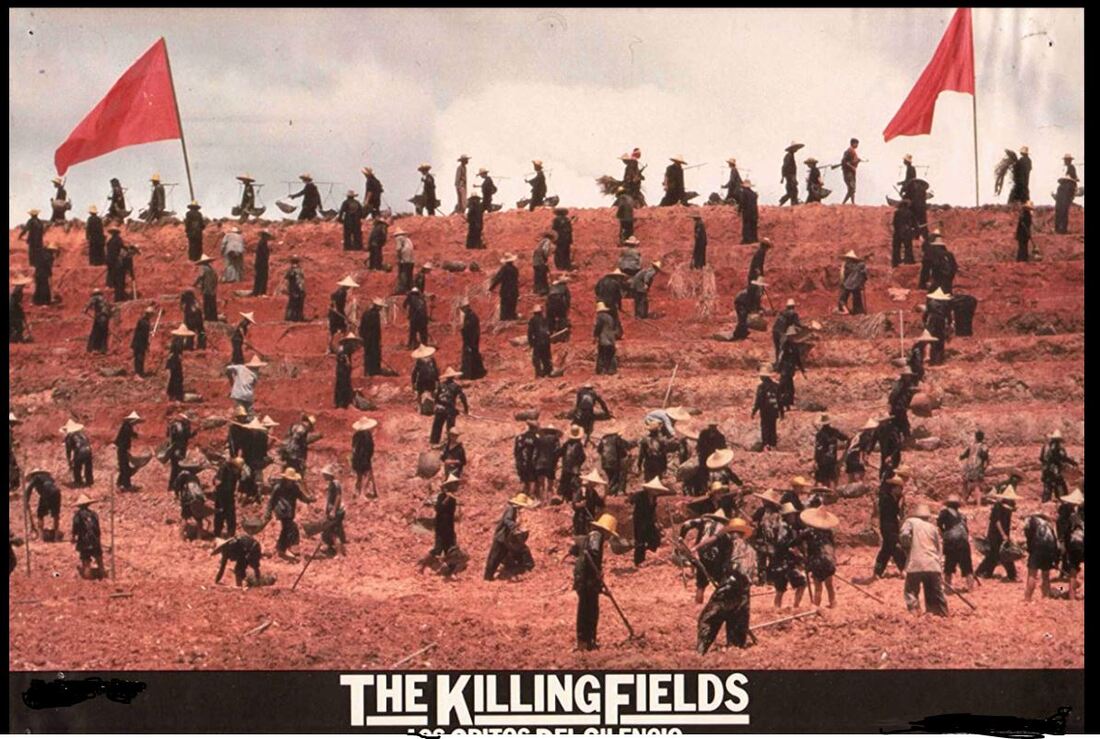

In year ten history class, my teacher Mr Kingsley put a video tape of the “The Killing Fields” on that we watched over a couple of lessons. I look back now and wonder just how important that was for my life, would I be sitting here now, fifteen years later, writing a review of the film as part of my own project to explain Cambodian history and the Khmer Rouge to a wider audience? Probably not. I think I owe this movie something for the journey that it influenced me taking.

There are a few things you can say about the film that are hard to argue against. For instance, I believe it is the best ‘movie’ about Cambodia made in the West, not that there are very many. It is also fair to say that it is an important movie, and the impact that it raising awareness about the tragedy that had occurred in Cambodia was beneficial. It is admirable in its attempt to recreate locations, events and people to a highly accurate degree. Lastly, I think the portrayal of Dith Pran by Haing Ngor is one of the bravest pieces of acting ever put to screen. Fifteen years since I first saw it, I would say that I have probably watched the movie more than ten times. Then, in preparation for a ‘commentary track’, I’ve made more of an effort to research the film itself and the characters portrayed in it, watched it through a slightly different ‘lens’ as they say. I re-read The Death and Life of Dith Pran, the article turned into a book written by Sydney Schanberg and the material which the screenplay is based, as well as Haing Ngor’s Survival in the Killing Fields, Jon Swain’s River of Time and also watched the Khmer Rouge Tribunal footage of Sydney Schanberg and Al Rockoff’s testimony. I tried to formulate my own ‘take’ on the film that I had previously not really bothered to do. I had, more or less, just viewed it as a good movie about a subject I care a lot about. My ‘thoughts’ about the film have been influenced very much by Al Rockoff, the photographer played by John Malkovich, in an answer to a somewhat bizarre question given the setting of an international tribunal of the Khmer Rouge leadership. When asked by the defence for Nuon Chea if he had seen the film, Rockoff went on a small tangential rant: “I always get asked that. For the first time back here in 1989, I keep getting asked, ‘you see killing fields? You see killing fields?’ I walk down the street, the tuk tuk drivers, ‘you see killing fields?’, of course I’ve seen the movie, many times. I have my own thoughts on the movie that may not be shared with the public because of how I’m portrayed in the movie. But I consider it a work of art. I might find some fault with how certain personalities are represented or certain facts. But its an important movie.” It is an important movie, even if some fault can be found with certain representations. I like The Killing Fields as a movie, it is an important movie with an important theme – but it is a movie. So my criticism of it as history must be tempered by that fact, that it was designed first and foremost to be a compelling experience for your average movie goer – not for the majority of Cambodians, historians or those with an interest in what happened in Democratic Kampuchea. However, the film – like historical writing – does decide what it shows and what it doesn’t, it frames the narrative in certain ways so that your average viewer comes away with an impression of a historical event. For instance, the impression we get of Phnom Penh and Cambodia generally is entirely focused on the US presence, the excess of US bombing, the failure of the US to stop the Khmer Rouge and finally in no uncertain terms Schanberg later blames the insanity of the KR on the effect of a few million tonnes of bombs dropped on them. Perhaps the cultural context in which the film was made explains some of that angle, the collective need to denounce the US after the Vietnam War, the lack of faith in government, the anti-war movement generally. But because the film is limited in its scope by its reference point of a western journalist bemoaning the way he treated his Cambodian colleague, we get an underwhelming explanation of what else happened or why it happened. Was the US involvement in Vietnam and Cambodia a contributing factor to the Cambodian nightmare? Sure, but it was one of many. The film also diverges from its own source material in some cases where, if it hadn’t, the whole story might have been made more apparent. In reality, Dith Pran’s exit from the French Embassy lacked a contrived scene of attempted photograph development, but it was no less dramatic. His throwing away of several thousand US dollars, taking on his new identity and getting through a KR checkpoint among the thousands of evacuees from Phnom Penh would have been very interesting to watch. Instead, in perhaps the film’s weakest scenes, the focus is placed on Schanberg in New York. We watch him regret, we watch him slump in a chair. We would have been able to guess his emotional state following his return to the US, but instead we need to be shown that the story is just as much about the US as it is about Cambodia, footage of Nixon, bombs and carnage leaving the audience with a graphic finger pointed at the reason for Democratic Kampuchea. The film spends roughly a quarter of the second half of the film still following the ‘main character’, Schanberg. This, in my mind, was an opportunity to commit to the Cambodian side of this tragedy, experienced by Cambodians, but the script still demands our viewpoint to be concerned with how bad the US should be feeling at this time. Again, here we come back to the idea that his is a movie, but the lack of subtitles in the Democratic Kampuchea section of the film still places the viewer as the outsider, as the westerner (generally speaking) who must watch in horror as the Cambodians descend into ‘insanity’ because of things we’ve done. Rather than a project that they decided upon and implemented. The other aspect of the film that I think does need to be criticised – even if it is primarily a movie – is the lack of violence. Cambodian audiences, historians and even those acting in the film (Haing Ngor) voiced their opinion that the film did not go far enough in its depiction of the brutality of the Khmer Rouge. You can notice in a few scenes the stunted length of Haing Ngor’s right pinky finger. That part of his finger was cut off during one of his three stints in a rural Khmer Rouge prison near Battambang. The other acts of violence he was witness to at these prisons are some of the most extreme that one can find in studying the regime. And while depicting acts of torture and gruesome violence itself may not have been possible due to ratings concerns, the film does not show the non-violent brutality of the regime. The masses of starving, the sick and the slowly dying. We are shown ‘the killing fields’, in a tremendous scene yes, but prior to this Pran is helped by a friendly young cadre and after his escape we have him in the company of a moderate commune chief. The percentage of time spent to showing the Khmer Rouge as violent killers is comparable to the amount shown of their accommodating nature. Yes, black and white, victim and perpetrator, these binary distinctions in a period of mass death lack applicability, but I feel the movie does not quite explore this theme satisfactorily – and perhaps goes too far in its attempt to show the grey area, rather than the tragic demise of more than a quarter of an entire population at the hands of one group – the Communist Party of Kampuchea. Alas, it is a movie, and it is a movie that I like very much. I wish it could have shown more of the story as it really happened, but perhaps that is only because I have learned far more about that story since I first saw the film. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the country, but I would certainly not tell them to stop there. |

AuthorLachlan Peters Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed